When I attend any antique wooden

boat show, the first thing my eye catches are those beautiful fine finishes

on those truly classic hulls. There is something about the look of a well

designed antique wooden hull, glistening on the water, with it's chrome

or polished brass parts accenting their sculptured-like lines that strikes,

I believe, all of us. The combination of natural wood and man-made

polished metal, to me is a very eye appealing experience. This article

is written expressing my thoughts on the execution of the time honored,

typical spar varnish finishing method used to achieve the deep warmth and

beauty of those varnished wood boats. And some thoughts on one other possibility

of finishing a classic wooden boat.

definitions

& a few thoughts

First of all. Marine coatings for wood

- a clarification. "Varnish" today is a generic name used by coating suppliers.

Many years ago, varnish was produced predominantly by boiling linseed oil.

In the last couple of decades, coating suppliers replaced real varnish

with a solvent-based (and recently water-based), polyurethane-based material.

This was done because polyurethane has overall, superior physical properties

than the former "boiled linseed-based varnish". These 2 coatings are a

completely different 'breed' from one another. Polyurethane is a petroleum-based

derivative product. But the name "varnish" and "spar varnish" seems to

have stuck with these marine coatings. I suspect marketing folks must of

thought that the name "varnish" was a product that had established name

recognition. So the chemical name was not used for the general public.

Anyways, this article will detail the application & polishing of a

"varnish" (polyurethane) coating. Which in this case, is a singular-component

(non-catalyzed), linear polyurethane. These polyurethane coatings are very

flexible, quite durable, (some coating companys also claim they are 'hard')

quite the opposite) and adhere well to other types of coatings and to it's

own type. They are relatively easy to apply by brush. But, as with most

coatings for wood, never 'bullet' proof. The wood itself is the weakest

link in this chain. Today, powder coatings & UV (ultraviolet cured)

coatings are superior coatings versus what was typically used for wood.

And because of environmental reasons, they are being use more today than

ever in wood finishing. The harsh conditions of a marine environment has

many problems for these types of coatings. The more traditional coatings

of Lacquers, Enamels and Polyesters are of different "families" of chemical

makeup. They will not be considered for this article. I would not recommend

these types of coatings for marine type finishing on wood. This article

also has a few thoughts on "automotive-type" urethane coatings that can

also be used for wood in a marine environment. The coatings are the plural-component

(2-part, catalyzed), hybrid, acrylic-urethane types. This product is fast

becoming the preferred coating for today's automotive refinisher. I think

they are a viable alternative coating for wood boat restorers who have

access to professional spray & safety equipment.

varnish

(polyurethane) vs automotive-type (urethane) coatings

After completing the varnish coating

on my old hydroplane, I have come to the conclusion that the truth of the

matter is the "automotive-type" coatings can produce a great shine quickly

and can be applied in a lot less time than "varnish". They have had tremendous

gains in their properties within last 5 years. The biggest benefits that

I see are the one-time, one-day, multiple application of coats and ease

of polishing. From an aesthetics point of view, these coatings are quite

clear. So if you want to have that "warm" amber look of varnish, you will

need to introduce a "amber" colored dye into the product to achieve the

look of "varnish". They tend to have a "plastic" look to them. Just a side

note, either of these finishing systems can be applied over epoxy coatings.

And I would recommend surface preparation using this product. It has many

useful properties that I will explain later in this article.

The drawbacks with "automotive-type"

'marine' urethane coatings are that you need to "professionally" apply

this coating. That means spraying and all the precautionary steps that

go along with atomizing a coating with air. Another factor is cost. Transfer

efficiency of the coating product to the surface is poor. At best, about

half of the coating is wasted in the air, due to the inefficiencies of

spraying a coating. Another drawback is total film thickness. They tend

to have much higher 'solid' contents. You can not keep piling on multiple

coats of this product. Some coating mfg's state urethanes can be built

up to about 20 mils (dry) thick, but I would never recommend going this

thick on a wood product. These are 'harder' type coatings versus "varnish"

and will have a greater chance of cold

checking or spider web cracking with the greater movement of wood versus

an alloy or non alloy type surface.

"Varnish" will be applied mostly

with a foam brush, which means close to everything you paid for will end

up on the lumber you are trying to protect. You can recoat very easily

and you can apply many coats. The biggest drawbacks with "varnishing" would

have to be the time length involved in the coating application and polishing.

Because of the physical properties of this product that give you all the

benefits described above, those properties also hinder the wood finisher.

"Varnish" has a very long, dry-to-touch, cure time. And you usually have

to wait 24 hours before recoating. And you need to resand (280 or 320 grit)

before applying the next coat. If temperature and humidity are ideal, you

can cheat and apply another coat over a 'fresh' coat, but you a taking

a chance. And even then, only one coat could possibly be applied. The marine

coatings just do not dry fast enough. Most of these coatings have a "window"

that you can recoat in. And some of these coatings have a narrow time frame.

Follow the mfg's suggestion. Practice on samples. The last thing you want

to do is need to sand a coat off because of an adhesion problem. I've seen

it more than not that when it comes to wood finishing, you will usually

pay dearly in time & money with your attempt to 'cut corners'.

"Automotive" Coatings:

If you are going to apply the automotive-type

coatings, and you sprayed the coating in a clean environment, you will

not have much dirt in the coating. If you do not want to put any more effort

into polishing, you're done. The coating will have a "orange peel" effect....but

it will be shiny...similar to what the Detroit puts out on the new cars.

But if you want a custom look, polishing will be relatively a simple process.

These coatings are 'harder' and polishing-friendly. To get the 'mirror,

wet look, wet sand with 600 grit and then 1200 grit. Followed up by polishing.

"Varnish" Coatings:

"Varnish" has a thin protective

film that is floated to the top as the solvents evaporate from the coating

you just applied. This abrasion resistant film helps the "varnish" prevent

marring and fine scratching. If you decide to polish the coating, you will

remove this protective film and your coating will be more susceptible to

scratches. Also, these "varnishes" are probably the worst coatings in the

world to polish. They are very "soft" coatings, which in turn, make it

difficult to polish. Some "varnish" coatings are nearly impossible to polish.....they

will have a "haze" to them after all your hard work. Remember, these coatings

were not developed to be polished and thus the physical properties of the

coating do not lend themselves favorable to polishing.

SIDE NOTE: For other arguments on

this subject,

click

here to read an article on the Land O'Lakes Chapter of the ACBS website

about this debate. It's titled, "Urethane-- A Viable Alternative to

Varnish?" by Sherwood Heggen. This article explains some of the differences

between using these two coating systems in a marine wood built hull. It

sounds like it is still being proved out, but you will have to decide for

yourself which is the route for your hull.

a

flawless finish

Unless the last coat was applied in

a perfect clean "coating-friendly" environment, you will have dirt, lint,

and other airborne contaminents will float into your wet varnish coating

during application and the relatively long, dry-to-touch cure time. The

washing the floor, perfect time in the day or evening, and the other rules

you hear and read about are never going to totally eliminate surface imperfections

caused by the little dirt and lint buggers. You can minimize the amount,

but you are fooling yourself if you think you will produce a totally flawless

surface effect in a garage or outside. Detroit spent millions researching

'dirt' in their automotive coatings finishing rooms and found most

of those were caused by humans. Lint from clothing being the #1 culprit.

These studies help develop the self-contained, enclosed & dust-free

spray booths. Robotics and deionizing areas for humans entering the finishing

rooms minimized or almost eliminated these little dirt 'buggers'. "Automotive-type"

coatings will be less prone to dirt and lint, because of it's physical

properties, (they don't seem to be have the same "magnetic" properties

as "varnish", but there will be, inevitable some dirt. With "automotive-type"

coatings, those dirt particles can be removed more easily with spot polishing

as opposed to polishing the entire hull. Varnish is nearly impossible

to spot polish.

So be it.....you're not happy with

the final result of your off-the-gun or off-the-brush coating.....

to

polish, or not to polish

That is the question many of you do-it-yourselfer's

ask yourselves after the wood finishing work is completed. Unless you are

coating a flat one-dimensional level surface in a small amount of time,

you will never achieve the correct, micro precision dry film that is required

to produce the reflective effect of a mirror. The reasons why a mirror

is so reflective (and I'm not talking about the silver nitrate that is

applied to back of the piece of glass) is because of a perfect flatness

of the glass itself. The fact that the glass is nearly perfectly flat combined

with the reflective coating on the back combines to reflect light perfectly.

No distortion in the reflectance is the sign of a quality mirror. Telescope

lens take this reflectiveness to the next level. Same principal applies

to any coated product. Most coatings are applied with brush or spray, and

that, combined with solvents that help smooth and flow the coating out

in an attempt to achieve that 'perfect' film level. But you will always

have a "orange peel" texture to the surface and this will distort the reflectivity

of the coating. You can see this by sanding the surface by a blocking the

coating will very fine sandpaper. This will dull the high spots and reveal

the amount of "orange peel" texture that is impairing the final goal of

a perfectly flat, reflective coating. Without sanding and polishing, the

coating's brilliance, shine or reflex can be high.......but to what degree?

There are instruments that measure

this and assign a number on a scale rating. We use them in our shop. The

Gloss Meter instrument reads this by bouncing a light off the surface and

measuring the amount of reflectance. But the difference that can be achieved

between a shiny pebbly and a mirror effect is the refinement of

the reflective surface. Usually, an acrylic enameled or urethane

surface that is sprayed well will score a higher gloss level than a polished

to perfection, glass-like surface. So the machine sees a difference of

gloss but the machine cannot 'see' quality difference. This is the difference

you can see from a factory applied coating and the custom

applied coating. The difference being - the surface imperfections have

been removed by the sanding/polishing process. So when you see a "shiny"

coating out there and you're amazed at the brilliance. LOOK CLOSER. Judge

the coating by it's reflective qualities. Next time you are at a classic

car show, look at yourself in the coatings of different custom paint jobs

from about 3 feet away. Are the details of your face as crisp as when you

look into a mirror or are they slightly distorted by a pebbly effect? If

they crisp and clean like looking into a mirror, then you are not just

viewing just a shiny coating, but instead a very refined work

of art. Years ago, it was rare to see this quality of work on custom

paint jobs, most of them were done with many coats of acrylic lacquer and

polished out to perfection. But today, with the improvements made to automotive

coatings, it's rare to see a car at a show that isn't painted and polished

to perfection or very close.

|

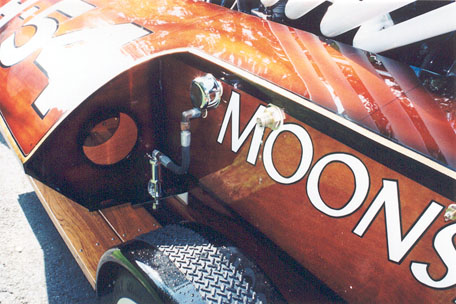

Moonshine Baby H-54 was clear coated

with Z*Spar Flagship #2015 "Varnish".

The graphics were sprayed with white &

black acrylic enamels (2-part) over the top of the Z*Spar after the clearcoat

was cured & polished. |

I

want it as perfect as I can get it

Unless you have tons of more time or

some more money to spend, perfection is a lofty goal to achieve with clear

coat wood coatings. The fact is you are coating a piece of wood and wood

was a living organism composed of a cell structure will always move in

the course of time. Any coating will only be as perfectly refined as the

structure it goes on. Temperature and humidity changes will move almost

any structure a coating is applied too. Even a mirror (the silver nitrate

on the back of the glass and the glass itself) degrades over an extended

time. Wood will continue to have movement, expanding and contracting. The

coatings for wood have more elastomers in the coating recipe than most

other coatings for this. This helps the coating stay pliable during the

surface contractions (a good thing). But this also means that all your

sanding and polishing work will eventually degrade slightly with time.

It will eventually form a "orange peel" texture from this movement. Although,

it will never degrade to the degree of an off-the-gun or off-the-brush

application of a coating. That 'orange peel' texture will eventually get

worse.

so

what gets me close?

A little thought, some extra time, money

and alot of 'elbow grease' will go a long way. If you have never attempted

wood finishing with marine coatings, practice on some samples before starting

on your wood hull. About 95% of your time goes into surface preparation

prior to the coating application and/or polishing. Don't butcher all that

hard work because you think you can wing it along the way. Your

final result will convey this.

before

you start

First......again.....make some samples......Perfect' everything on your

samples before proceeding. I think most folks will be glad they did. It will give you the

satisfaction of knowing what you are going to end up with. It will also

allow you to make changes, especially with the color. With your samples,

you can figure out what sanding steps are required, (and which sanding

steps are NOT required), amount of stain and strength needed, proper amount

of time to leave the stain on before wiping off, diagnose potential problems

with sealers, and topcoats, (and polishing....remember certain "varnishes"

will produce a haze). If you want that look, now is the time to find the

correct "varnish". Peace of mind has it's dividend's. With wood finishing,

it's best to find all the "surprises" on a scrap piece of lumber and not

your prized hull. You can make changes easily with samples. On your sample,

mask off each of the steps you take with masking tape, after you complete

the sample, removal of all the masking tape will give you a "Blueprint"

for your wood finish. Remember.....after it's all done.....you're the one

who is going to have to live with the results.

surface

preparation

Sanding....If you are finishing plywood, look at the thickness of your

top "ply". This top veneer of the plywood, even from the same manufacturer,

can and will VARY. Be sure you have enough "meat" to work with if you are

going to sand with a heavy grit. By the way...a few years back the American

panel manufacturers were going to adopt the European standards for veneer

thickness. Most European & Asian grades of plywood for furniture have

a 1/40" veneer thickness. Americans opted not to go to this standard and

stayed with the 1/28". This is good. It is almost impossible to refinish

(from the sanding that is involved) a Non-American made veneered panel.

Producing quality marine grade plywood was given up being produced by the

American manufacturers. Fortunately although, with marine grade plywood

produced by the Europeans, I've found there is a significant thickness

on the top ply, face veneer, closer to 1/16". They were thinking. But look

first before proceeding.

Sand only enough to get out the surface imperfections. If you have

a scratches and dents, soak a towel with hot water and apply to the scratched

area. This will raise the grain and in most cases lift the surface of the

veneer or lumber so you can sand out the area level. Don't trying sanding

out imperfections without raising the grain, you may sand through the face

veneer, then you will have a real problem. Sand with the grain and

a level block to support the sandpaper if using anything from 35 grit to

280 grit. Use the finest grit possible to remove imperfections. At 320

grit sandpaper, you can usually get away with a DA (dual action, circular)

sander and not show circular marks from the stain that will highlight

the sander scratch pattern. You can use a random orbital sander but I prefer

a non orbiting sander for this step. A straight-line sander is going to

give you the best job, but they are slower. If you are not sure, sand with

a block in the direction of the grain. For final sanding, this will

not take much more time. Change your sandpaper frequently. Sandpaper is

relatively cheap compared to your labor time. Silicon carbide coated on

the paper is best for wood. But the "sharpness" of the silicon carbide

will degrade quickly, so again, keep changing sandpaper for the best, most

even results. Another note - Quality sandpaper is a must. If you have ever compared different mfg brands of sandpaper you will know why. Don't be cheap - you get what you pay for. For the lower

grades (up to 120 grit), there is not much difference between manufacturers,

these are essentially "filing" grades of sandpaper.

Remember, your stain work will only be as consistent and even as your

last couple of sanding operations were.

a

few other notes worth mentioning...

Before you start sanding, "wash" your hands with wood dust. If you have

any oils from your hands on the wood surface, wash the wood area with Naptha.

Also, another "trick" used by wood finishers is to pour Naptha on the entire

wood surface. It will give you a visual look of what the surface will look

like after all the clear coating is done. It will show up everything.

When you happy with your results and think it's time to apply some

stain (or sealing the wood, if not staining), vacuum the dust off, then

use dry, clean, compressed air to blow the wood dust from

the wood pores. If you use a tack rag, wipe very gently. That's a shellac-type

of product they impregnated into that cheesecloth that makes them tacky

and this product will show up if any gets on the wood surface when stained

or varnished over.

applying

the wood stain...

SAFETY First. With most stains, you're dealing with flammable solvents.

Protect yourself, your hard work, and your prized possessions. Make sure

environmental conditions are right. Next make sure it is warm and

dry out. After you have practiced on your samples and think you are ready

to color that wood.......remember....this is not a race. One of the reasons

it is hard to get anybody interested in wood finishing is because it's

very dirty work. Most people just want to get it over with. So take your

time and be very methodological towards this operation. Try to apply the

stain inside or at least in the shade. Lighting is critical. Have lots

of it. Many a bad finishes were due to poor lighting. Also...view your

work from different angles to 'see' it all. You probably don't want to

see any surprises when you're done and take it outside in the bright sunlight.

The staining application operation will work the best with 2 people

when staining a very large object such as a boat hull. One to apply &

one to wipe off the excess. If working by yourself, map out your strategy.

I stained my hull's bottom first, followed by the sides, chines, and sponsons.

Using all natural breaks in the hull to your advantage. After all finishing/topcoating/

rubbing is completed, then flip the hull, mask off all your finished work

and then finish the decking.

From your samples you will already have figured out a time to let the

stain sit before the wiping off operation. Make sure your stick to your

schedule. Generally, wood will only absorb so much stain. But stain formulations

vary, so follow your own time schedule. Apply the stain in a circular,

downward movement, making sure you are getting it's pigments loaded into

the pores really well. If you did larger samples you will have figured

out that. Stain wiped off too early? The stain may not give you an even

coloration of the pores and may look spotty. Some stains, if left on too

long, can darken the wood past where you wanted it. If this happens,

you can lightly steel wool or scotchbrite off some excess, but be careful.

This effect can look different than what you are trying for. Most wiping

stains are formulated for a "clean wipe". All excess stain is removed.

Make sure you have many absorbent, lint free rags available.

The stain is going to bring out all imperfections. If you missed a

scratch or dent, sand it out now, yes....during the staining operation,

if you wait until after the stain has dried, and then try to fix and restain

the area, you will have a "halo" around that repaired area.

When you done, stand back and thoroughly go around your hull looking

for areas that don't look right. A even application, followed by a clean,

even wipe will give you the results that you achieved with your samples.

Most wipe stains require an overnight cure. Follow this direction.

If you start applying your clear coats before a complete cure of the wiping

stain you will probably have adhesion failure.

One Very Important Note: Wet all your rags down with

water if you used a solvent-based stain when you are done staining. The

oils used in these stains can, and will, self combust if compacted enough

and not given enough air to dry. I've seen many fires in the finish room,

because of this. I am always surprised this is not even written on some

brands, or the ones that are supplying this information, written larger

on solvent based stains that are sold to the public.

sealing

the wood prior to topcoating

First....you need to seal the wood and allow gases that are in the pores

of the wood to escape. Mahogany and Oak are two wood species that have

deep pores and need to gas out as the first coat begins to cure. Species

like maple and cherry do not have pores that are very deep and are not

as prone to this phenomenon. What is happening here, is the sealer coat

is "forming" a skin on the top surface and the gases have not all escaped

from the wood surface. As the gas tries to escape, tiny bubbles will appear

in the first coating. These are commonly known as blisters. You

DO NOT want these, as they are nearly impossible to remove without starting

all over. Even a no-stain finish can show these. Do not start piling coatings

on the surface thinking these will disappear. You will only make them worst.

Sand off and restart. If you prepared you samples first, you would have

seen this and prepared your sealer accordingly.

Secondly....humidity level....if it is humid out, you will get water

trapped in your clear coat as it dries. Do yourself a huge favor and wait

for another day. Moisture trapped in the coating will look like a white

haze or a bloom. Another mistake that requires a full stripping and sanding.

If you have some "blooming" after the clear coat has cured to touch, you

can heat up vegetable oil and pad the surface. This will resoften the coating

and allow the moisture that is trapped to escape on certain coatings. Another old trick that

still works with even today's hi-tech coatings. (I remember my mom crying

after she ironed a shirt on top of some towels on her new coffee table.

I cooked up some hot, not boiling, oil and showed her how to fix this dilema.

This also works for water spots on your furniture). After any clear coating,

move the object indoors or put up a tarp. The nighttime dew sitting on

any freshly clear coated surface, even after 16 hours, may "bloom" the

coating.

sealing

the wood with epoxy prior to topcoating

The sealing step is where I like the epoxy coatings. You may use this product

under either clear coating system you are electing to use. With a stained

hull, the best property of epoxy is two-fold. The first being, it can go

on most open pored woods, full strength, with out 'blistering'.

Just make sure you apply a very thin film for the very first couple of

coats. No excessive rolling or brushing here, you might want to use foam

brushes for the first few coats.

Secondly, epoxy has very high build, and you can apply multiple coats

after the product has reached a dry to touch state. I started in the early

morning and applied as many coats of epoxy as I could before the work day

was up. After a 24 hour cure, you will have a encapsulated finish, with

the chances of sanding through this finish very remote. You still want

to be cautious around edges and corners when sanding, but for the most

part, you have just "locked in" all your staining and woodwork with a very

thick, hard, and durable film. If you have ever sanded through the stained

finish, you'll appreciate this property.

topcoating

After preparing the coating for topcoating

by sanding, vacuum and tack off the dust. If applying "varnish", I pour

out a line and using a wide foam brush, work left to right out from any

end. I worked out about 2 feet and started the next row. As I near a wet

surface I lightly overlap the previous coating. Add solvent, (as, and/or

if), required to get a level and even flow out. Work quickly and try to

get a heavy and even coat applied without runs.

Again.....watch temperature and

humidity levels, work indoors and try to keep bugs to a minimal. I have

no suggestions for bugs other than if you have the luxury of time, coat

before they arrive in the spring or after the first hard freeze. If they

are just 'build-up' coats, don't sweat it, as you cn sand them out before

the next coat. For final coat, if you are polishing your coating, no problem,

but watch your coatings flash and have a fine, needle-nose, or hemostats,

ready to pluck them from your wet surface. I also found that having screens

in your garage windows work. Try to keep as much fresh air coming in as

possible for the finisher.

Air dry at least 24 hours. If you

had any runs, use a razorblade to scrape then out. Then, sand with 320

grit and a block for those areas. Now go over the entire coated area. I

sanded this step with my electrical, random orbit, palm sander. I've had

this Porter Cable sander for 20 years now and it is the only time I have

found a good use for this sander. It does a fast, near perfect sanding

job with these "varnishes".

"Automotive-type" coatings, follow

product data sheets directions. You will need to ask for these when you

buy the coating. They are usually not labeled on the can. Generally, you

will apply 3-4 coats total. Most people just keep putting on coats until

they are just about out of coating.

how many coats do you

want to apply?

Well, most of us would prefer just one

but we're talking wood finishing here.......so.....If you were thorough

with your samples you will have figured this out. I went with 9 coats

of "varnish" before I thought I had enough varnish applied. Most "varnishes"

are about 25-30% solids. That means you will apply about 6 mils of wet

varnish per coat. After the solvents evaporate, this will leave a 1.5 mil

thick dry film. After sanding, you will have about 1 mil of dry

film left. Multiply this dry film by 9 coats and this will give you a 9

mils total of dry film. This is a sufficient base for which

to sand and polish out. Also, this film thickness allows for 1 additional

refinishing jobs before reaching that 20 mil film limit for varnish. This

will also make a good sanding base for those refinishing jobs years down

the road. If you do not polish, this will give you a nice, deep look. By-the-way,

most "automotive type" total dry film thickness is 6-7 mils thick and a

typical "automotive coating" can have 2 additional paint jobs done before

the whole thing will need to be stripped completely. But remember, I would

not recommend this film thickness for wood. Also, I used almost 2 gallons

of "varnish" to complete my 19' 7-litre hull.

"Automotive-type" coatings (because

of their higher solid content) generally need only 3 or 4 total coats and

can be sprayed right on top of the next coating, as soon as the previous

coating is dry-to-touch. The big plus here is you are done in 1 day.

If you are handy with a spray gun,

I would highly recommend you spraying the varnish for the last coat. This

will give you the best look and make for a easier polishing job if going

that route.

spraying the last coat

with "varnish"

If you decide to go this route for the

last coat, here's some tips for you. I recommend this, but you'll have

to decide for yourself if you want to do this. Spraying a coating will

always leave the best finish, bar none, to any coating application using

liquids. But some skill is involved with handling a spray gun. You need

nice, even, consistent movements. Runs, dry-spots, inconsistent and

an uneven coating will be your worse finishing nightmare. If you have even the slightest

doubt with working a spray gun, I wouldn't advise spraying any type of

coating. If you're confident, but don't have much experience with spraying,

again make samples, something 3-D, if you're happy with the result, go

for the hull. It helps to think and move like a robot.

My favorite spray gun for applying

the heavier viscosity type coatings were the old Devilbiss MBC spray guns.

These babies could atomize most coatings into very fine particles

for the perfect finish. They have not been around for a long time. But

the standard automotive refinishing spray gun handles the varnish very

well. The spray gun I predominately used was the Devilbiss #JGA-502-30EX (30EX being the cap and needle size),

which handles reduced varnish just fine. This gun has been a standard in

the automotive refinishing industry for quite a while, until the new technology came along. The JGA was a "conventional"

spray gun that produces good atomization, but transfer efficiency is not

very good. HVLP (high volume, low pressure) spray guns would probably work

if you have one and can get alot of product through the gun with some very

large tips. I personally don't care for them for small batches and staining

work, (mostly because I don't like the atomization of the finishing material)

but they are standard issue in California because of the state-mandated,

transfer efficiency ratings these spray guns produce. We use HVLP in our

high volume (topcoating) area in the finishing room. They use high amounts

of air at very low pressures to atomize the spray. This helps the spray

not "bounce" off the surface you are spraying. If I had this set up in

my tool box, I probably would have used it. If you have a spray gun in

your toolbox, try it on some samples and see if you get a smooth, heavy,

and even coat applied, which is the main objective here. No sense in buying

a new tool if you have one that will work. I get a kick out of seeing all

the ads for these fancy and outrageously priced spraying equipment setups

you see in the various do-it-yourself magazines. They also have these wild claims to 'em....Snake

oil...save your money if you don't own a spray gun yet. Just buy a standard

gun like above..about $200 bucks with a 1-quart spray cup (you'll spend

a little more with the stainless spray cup). It's very versatile and well

rounded for general spraying. The spray gun has all stainless passageways

throughout the gun. This will allow you to use it for water-based finishing

products and you won't have to worry about rusting anything. If you clean

them up right after each use, they will last you a lifetime. Adjust the

solvent reduction until you achieve the right "smoothness" to the coating.

Keep adding reducer just enough to spray a level coat and no more. Warm

the "varnish" if its cold out before spraying. (Careful, you're working

with big-time flammables here). A glue pot works best. It will help

lower the viscosity to a sprayable consistency without having to having

to reduce with too much solvent. Which with varnish, will be predominantly

mineral spirits. I also added in some naptha, which is a much faster evaporating

solvent than mineral spirits. (Old School was - 50% Naptha & 50% Mineral Spirits is

roughly what lighter fluid is). The key here, being to get a smooth, level,

and heavy coat applied, with no runs...that's the trick, isn't it!. If

you reduce (or thin) the coating too much, you will not get enough of a

dry film left on the surface to cover and fill in the 320 grit sanding

scratches and this is not good. Use a fine mesh strainer when pouring into

your spray cup. Double then up. Spray outside with just a light wind. Move

any vehicles, pets, and children. Varnish spray droplets are big, sticky,

gooey, blobs just waiting to ruin anything it lands on. If you don't like

your neighbors, this coat you are spraying will surely piss them off, so

plan accordingly. (That's why I live in the country).

Save your lungs and wear a cartridge-style,

organic respirator. Wear old long sleeves shirt, hat, and a pair of pants

you don't mind ruining. Or better yet, buy a cheap Tyvek suit for a few

bucks. Use disposable surgical gloves. I always have a box of these in

my garage....blue nitrale works good. If you wear glasses, they will be

'spotted' after you put this coat on. You will have a nice ring around

where your hull was in the driveway, so prepare for that unless your wife

doesn't care how that looks. You are going to probably be breaking a few

environmental and fire-safety laws, so you didn't read this here. PERFORM

this at your own risk!

Figure out which way the wind is

blowing and have it blowing on your back. Start spray direction close to

you moving right to left, back and forth, with moving the gun away and

spraying so all the overspray falls on the area that you are about to spray.

50% overlap each spray pass. Set your air pressure, at the gun, for about

50-65 pounds. "Varnish" typically likes to be sprayed at a higher air pressure

than alot of other types of coatings to get a good, even coat. Open up

the material control valve on the spray gun most or all the way and adjust

your fan width to give you a 8" width at about 8" away.cure

timeFor "varnish" I would wait at least

30 days before polishing. If you know you are going to polish, you can

sand after about 2 weeks and this will open up the pores in the coating

and promote a harder and faster cure. But still, let it sit for another

2 weeks.

If you used an "automotive-type"

coating, I would start sanding and polishing in about 14 days.

final

sanding before polishing

With "varnish", you should be able to

start with 800 grit if you sprayed the last coat. If you applied the last

coat with a foam brush, experiment with 400 or 600 grit to see if you need

to go this route. After 800 grit, I followed up with 1000, 1200, 1500,

2000 grit. Sand with rubbing block and a spray bottle full of warm water.

Keep the surface wet and do not push down on the block, let the

sandpaper do it's job. Human spit aids greatly in lubrication for this

step. My wife was laughing at me as I was spitting all over my hull, but

that's were the "spit-shine" term came from. Start a 2'x2' area. Get a

squeegee and use it to see what you are doing. Buy a large box of diapers.

The old style, 100% cotton, washable ones. These are getting harder to

find. Completely sand the

entire surface before moving on to the next grit. When you have completed

that grit size, on the next grit size up, you will want to sand in the

opposite direction. This method allows you to see easily that you have

removed the 'scratch' pattern from the previous sanding step. Keep the

surface clean, with these fine sandpaper sizes, you do not want to get

a chunk of anything that will gouge the surface.

On the 2000 grit, you can sand in

a circular motion with the sandpaper and sanding block. Keep the bottom

of your sandpaper clean. You can usually 'feel' if a bigger chunk of something

gets on the paper. Remove it immediately by getting fresh sandpaper.

With "automotive-type" wet sand

with 600 grit and then 1200 grit. You may need to finish up with 1500 grit

depending on the coating you used. To determine this, sand a small area

with 1500 grit and start polishing equally on both grit samples and see

if you need to sand with 1500 grit. If there's hardly any difference, you

can forego another round of sanding.

polishing

The buffer I use is a Milwaukee variable

speed 0-1750 rpm. I run it at full rpm. The guys at the shop use the Black

& Decker, because they make the lightest's polishers that we've been

able to try. I would not recommend a faster RPM for varnish. The bonnet

I have always used are called Round Up made by SCHELGEL. Part #890C.

This bonnet has a 1-1/2" pile. These are like the old lambs wool bonnets.

You will want the bonnet that is held on by a nut in the middle against

the hard rubber backer for the bonnet. Do not buy the tie-on ones that

have a string that attaches it to the pad. Any good automotive body supply

shop should carry these, they have been around for years. If not, the 3M

bonnets work okay. I would get two bonnets, one for the actual buffing

and one for cleaning up.

To get the feel of a buffer and

if you have never polished a coating out before, maybe try to use the foam

3M pads.....they were developed more for the 'rookies' at the body shops.

Their best feature is it makes it hard to "rub through" the coating. If

you're quick to learn and want the professional machine, use the bonnet

with the heavy pile and hard rubber backing pad. Just go easy near those

edges. Also, square inside corners are impossible to machine buff, so plan

accordingly. The polish I use is 3M FINESSE-IT II part #051131-05928. This

will be the only polish you should ever need. You will want to buff outside,

preferably on a somewhat windy day. You will have lots of lint flying around.

Work a 2' x2' area. No more, no less. Squirt a bead about 4" inches long

for that area. You usually need 2 applications of compound over a 2' x

2' area up to the gloss we all want to see. Clean up the bonnet often.

It should not be saturated (wet) or crusty (dry). To clean the bonnet,

hold the machine between your thighs and take a screwdriver and hold it

about 45 degrees to the pad. Power up the buffer at full speed and move

the screwdriver up and down. HOLD ON TO THAT SCREWDRIVER! They make a "spur"

for cleaning bonnets, but save your money. The screwdriver works just fine.

You will see the pad clean up as you move it back and forth. Get used to

cleaning your pad after every 3-5 applications of polishing compound. You

will see that cleaning the pad often will help you keep that pad nice and

fuzzy. Do not polish on the same spot very long. Keep moving the

buffer around left to right, then up and down. Use medium pressure when

you first start the buffing, then light pressure as the compound fades

away. Feel the surface right away. Is the surface too hot? It should be

slightly warm. That's it. Following these directions should bring the gloss

up, with a haze-free effect. If it's got a haze to it, you didn't recognize

that in your sample that you should had made to confirm you have a "buffable

varnish".

If it is an "automotive-type" coating

you are polishing, you will have no problems if the coating was properly

catalyzed, reduced, sprayed, cured and sanded properly. It will polish

out with ease compared to the "varnish" coating. With these catalyzed urethanes,

you can polish at a higher speed (up to 2600 rpm).

clean

up

Get some 3M Perfect-It Hand Glaze part

#05997 or 3M Imperial Hand Glaze part #05990 (available at the local auto

body supply shop) and using more of them diapers or sweatshirts. Apply

it like a wax. Wipe on, let it haze, and then wipe off with a clean cloth.

This will even out the polishing work and swirls and provide a protective

coating to your surface. Apply this material whenever detailing is needed.

It's good stuff.

That's it! If you took your time

and did everything yourself, you have learned a new trade, probably saved

yourself about $5000 bucks, and if you were thorough, should have the concours

quality wood boat finish. |